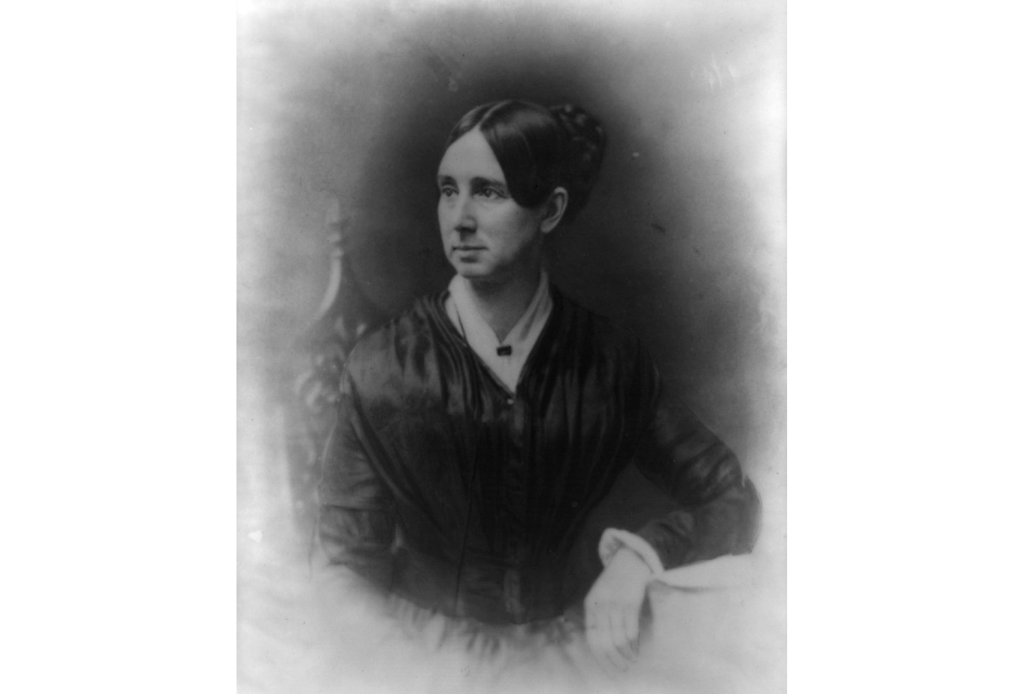

Dorothea Dix

Credit: From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Licence: This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

| Giver: | Individual |

|---|---|

| Receiver: | - |

| Gift: | - |

| Approach: | Philanthropy |

| Issues: | 10. Reduced Inequalities, 16. Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, 3. Good Health and Well-Being |

| Included in: | Generosity and Health |

Dorothea Dix (1802-1877) was an American social reformer who dedicated her life to championing the human rights of people with mental illness. As she demanded compassionate care for people with psychiatric conditions, Dix exposed the abusive and neglectful treatment prevalent in the mid-19th century, while contesting the idea that mental illness was an incurable moral failing. With an extraordinary empathy that may have derived from her own mental health challenges, Dix helped establish new standards for holistic, therapeutic mental health care that remain relevant today.

Dorothea Dix was born in Hampden, Maine, in 1802. Poorly cared for by her parents, she moved to Boston in 1814 to live with her wealthy grandmother. Dix began teaching at an early age and established an elementary school in her grandmother’s mansion in 1821. Alongside her teaching, she published numerous books for young readers and was active in Boston’s religious and intellectual circles.

Amid ongoing struggles with depression and respiratory illness, Dix traveled to England in 1836 for a period of convalescence. As a guest of the philanthropist William Rathbone, Dix met prominent English social reformers of the day, including Samuel Tuke, a Quaker proponent of “moral treatment.” A then-innovative approach to mental health care, moral treatment emphasized kindness and patience, rather than physical punishment and control. Dix observed this model of care in practice when she visited the York Retreat, a mental health facility founded by Tuke’s grandfather.

Following her return to Boston, Dix volunteered to teach Sunday school to women in the East Cambridge Jail. There she discovered people who had been deemed “insane” confined as criminals under brutal conditions – undernourished, living in filthy cells, often in chains.

Taking up mental health reform as her life’s mission, Dix investigated the treatment of people with psychiatric conditions in prisons, almshouses and asylums across Massachusetts, documenting her findings in unflinching detail. In 1843 she submitted a written testimony of her observations to the state legislature, appealing for their attention to “the strong claims of suffering humanity.”

Having spurred legislative action in Massachusetts, Dix took her campaign across the country. In keeping with the principles of moral treatment, she argued that people with mental illness would benefit from clean, spacious surroundings, structured daily activities, intellectual engagement and bucolic scenery. By the time of her death in 1881, Dix had influenced the establishment of 15 state mental hospitals and 17 privately funded asylums, as well as the improvement of many other facilities.

Contemporary biographers have criticized Dix for her failure to support the abolitionist and women’s rights movements of her day. While Dix’s progressivism was notably limited, she must be remembered nonetheless for the role her generosity, compassion and advocacy played in transforming attitudes and treatments for mental illness in the U.S. and beyond.

Contributor: Erin Brown

| Source type | Full citation | Link (DOI or URL) |

|---|---|---|

|

Brown, Thomas J. Dorothea Dix: New England Reformer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998. |

- | |

|

Dix, Dorothea. “‘I tell what I have seen’–the Reports of Asylum Reformer Dorothea Dix,” American Journal of Public Health 96, no. 4 (April 2006): 622-25. |

https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/epub/10.2105/AJPH.96.4.622 | |

|

Gollaher, David. Voice for the Mad: The Life of Dorothea Dix. New York: Free Press, 1995. |

- | |

|

Gollaher, David L. “Dorothea Dix and the English Origins of the American Asylum Movement.” Canadian Review of American Studies 23, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 149 – 75. |

https://doi.org/10.3138/CRAS-023-03-07. | |

|

Michel, Sonya. “Dorothea Dix; or, the Voice of the Maniac.” Discourse 17, no. 2 (Winter 1994-1995): 48–66. |

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389368 |