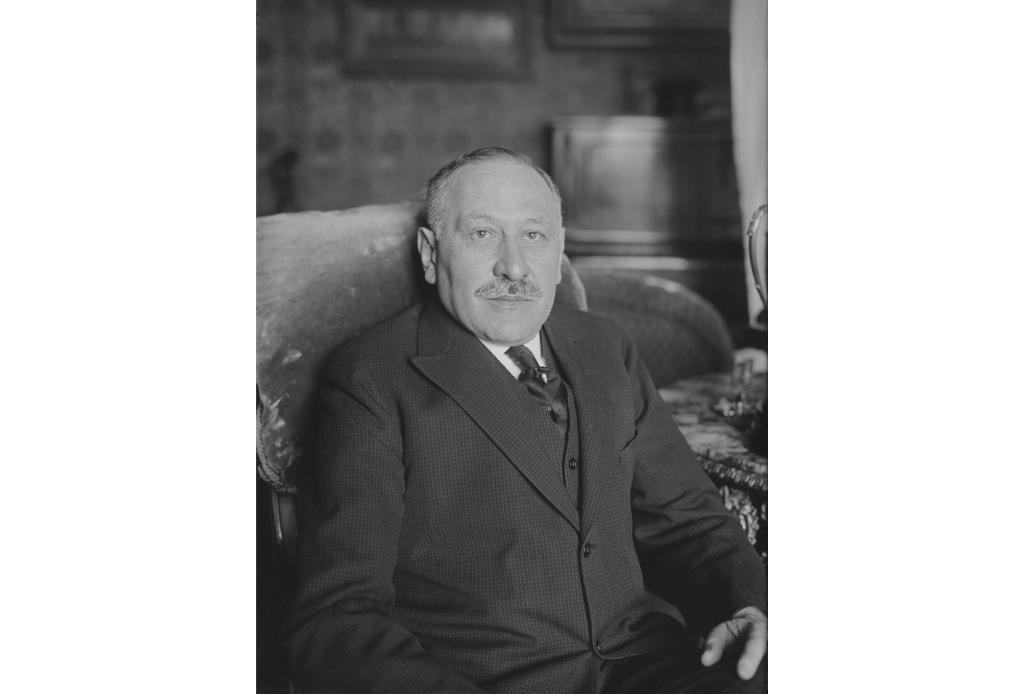

Julius Rosenwald

Credit: The Everett Collection via Canva.com

| Giver: | Individual |

|---|---|

| Receiver: | Other, Registered Organization |

| Gift: | Money |

| Approach: | Philanthropy |

| Issues: | 10. Reduced Inequalities, 16. Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, 4. Quality Education |

| Included in: | Philanthropy and Education, Private Foundations |

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) was an American businessman who made his fortune at the helm of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Unorthodox in his philanthropy, Rosenwald was staunchly opposed to perpetual endowments, believing that charitable foundations should give ambitiously to address the social needs of their own time, with the understanding that future generations would do the same. He is best remembered for the Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative, which created unprecedented educational opportunities for Black children in the South during the Jim Crow Era. As an early proponent of the “give while you live” ethos, Rosenwald has also exerted a lasting influence on the theory and practice of modern philanthropy.

Using His Good Fortune for the Common Good

Rosenwald was born in Springfield, Illinois, to German Jewish immigrant parents of modest means. Midway through high school he abandoned his formal education to follow his father into the clothing business. His career eventually led him to Chicago, where he took an ownership stake in Sears, Roebuck and led the company to become the country’s biggest retailer. Rosenwald was a millionaire by the age of 33, and his wealth continued to grow exponentially.

A fundamentally modest man who credited his success almost entirely to luck, Rosenwald regarded himself as merely a trustee of his fortune, with a duty to use it as effectively as possible for the common good. This attitude was significantly shaped by the teachings of Emil Hirsch (1851-1923), the eminent rabbi of Chicago Sinai Congregation, who emphasized the Jewish concept of tzedakah, or righteous giving, as a moral obligation and the highest aspiration of a society. Hirsch inspired Rosenwald’s ad hoc giving to various Chicago organizations and entities, including the Associated Jewish Charities, the University of Chicago and Jane Addams’ Hull House.

Developing His Own Approach to Philanthropy

Rosenwald rejected the idea of unconditioned handouts. For philanthropy to be more than a short-term palliative, he believed, it must foster genuine self-help. This thinking informed his support for efforts in Chicago and other cities to establish Black YMCAs, where underserved African Americans could pursue physical, mental and spiritual self-improvement. Rather than fund the projects outright, however, Rosenwald pledged USD 25,000 to any U.S. city that could raise another USD 75,000 for their facility. As a tool for catalyzing local investment in a project, the challenge grant proved hugely successful, ultimately leading to the establishment of 25 Rosenwald-subsidized Black YMCAs and three YWCAs around the country.

Rosenwald pursued a similar strategy with the Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative, an effort to create access to education for Southern Black children who were excluded from existing public schools under segregation. The project arose in 1912 in collaboration with Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute and the nation’s foremost advocate for Black self-help through education. With matching funds contributed by rural Black communities and additional support leveraged from local and state governments, Rosenwald supported the construction of nearly 5,000 schools across 15 Southern states over the course of 20 years, dramatically improving educational outcomes for the millions of Black children who attended them.

Giving with Immediacy for Long-Term Benefits

In 1917 Rosenwald created the Julius Rosenwald Fund to manage his ever-expanding philanthropy. With the stipulation that the fund must spend itself out of existence within 25 years of his death, it became the first major private foundation whose giving strategy was galvanized by a planned voluntary “sunset.” When the Rosenwald Fund shuttered, ahead of schedule, in 1948, it had given away the equivalent of roughly USD 800 million in today’s dollars, bringing the total of Rosenwald’s donations close to USD 2 billion.

Perhaps most significantly, Rosenwald’s insistence on a limited time horizon for his philanthropy spurred investment in innovative approaches to solving social problems. In “The Trend Away from Perpetuities,” which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1930, Rosenwald wrote: “The real contributions of philanthropy are not so much in money alone as in the support of new ideas or agencies which may prove to have great social value.” Indeed, he continued, “Real endowments are not money, but ideas.”

Contributor: Erin Brown

| Source type | Full citation | Link (DOI or URL) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication |

Aamidor, Abraham. “‘Cast down Your Bucket Where You Are’: The Parallel Views of Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald on the Road to Equality.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) 99, no. 1 (2006): 46–61. |

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40193910 |

| Book |

Ascoli, Peter M. Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006. |

9780253112040 |

| Publication |

Ascoli, Peter M. “Julius Rosenwald’s Crusade: One Donor’s Plea to Give While You Live,” Philanthropy, May/June 2006. |

https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/magazine/julius-rosenwalds-crusade/ |

| Book |

Diner, Hasia R. Julius Rosenwald: Repairing the World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017. |

9780300203219 |