Meitheal

Credit: Canva

Licence: Photo Images

| Giver: | - |

|---|---|

| Receiver: | - |

| Gift: | Time |

| Approach: | Reciprocal Gift |

| Issues: | 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities |

| Included in: | Mutual Aid |

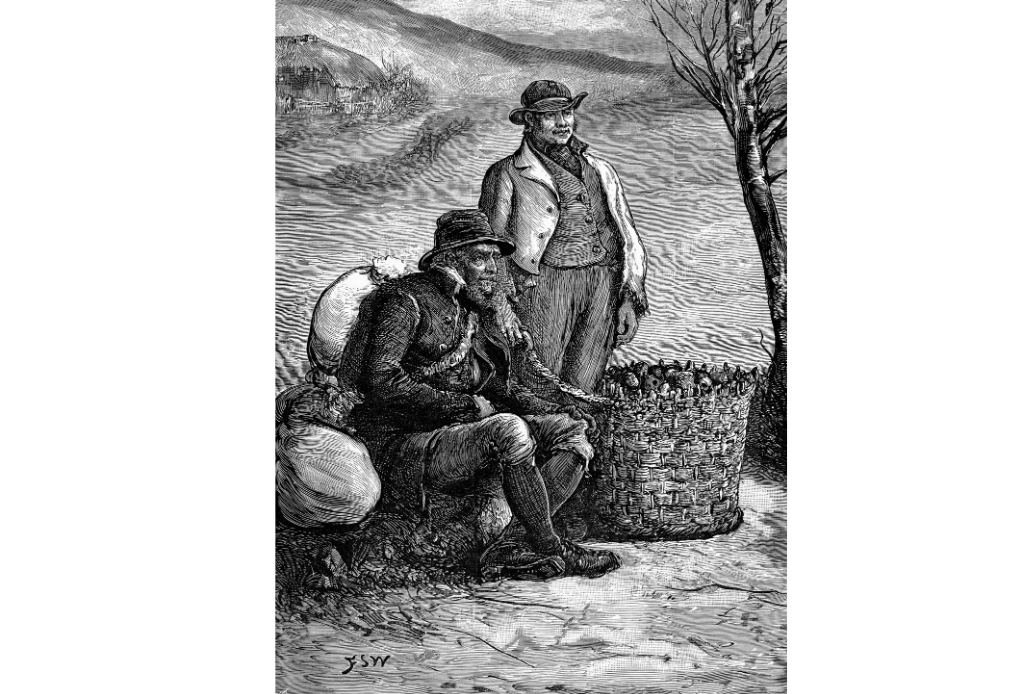

Meitheal (pronounced meh_-haal) is an Irish word referring to a gang or crowd of voluntary workers who come together to perform cooperative labor on behalf of a neighbor in need. Meitheal may also refer to the event of the work party itself, as in: _When the potatoes were ready, we had a meitheal to dig them up. A centuries-old practice, the _meitheal _was a critical form of mutual aid in Ireland’s pre-industrial rural communities, where labor-intensive seasonal tasks, such as planting and harvesting crops, were too much for a single household to accomplish. Although the traditional _meitheal _has largely faded from daily life in 21st-century Ireland, the _meitheal _spirit – with its emphasis on community solidarity, reciprocity and common purpose – remains vital in the Irish consciousness, inspiring everyday gestures of neighborly generosity and new collaborative approaches to addressing social needs.

Generations ago in rural Ireland, neighbors (anyone living within a day’s easy walk) regularly formed _meitheals _to help each other tackle large and often time-sensitive jobs, such as planting and harvesting potatoes, threshing oats, gathering hay and cutting turf. A team of men convened at one farmer’s field on a given day, with the understanding that this farmer would join the next _meitheal _whenever the need arose.

In addition to supporting economic livelihoods, the _meitheal _was also a social occasion. The _meitheal _crew customarily ate breakfast and dinner together, with food prepared by the host farmer’s wife. Completion of the work often gave rise to celebration, with storytelling, music and dancing into the night. Women also participated in _meitheals _of their own, as when many hands were needed to card and spin newly shorn wool.

Even as 19th century advancements in farm machinery reduced the need for volunteers in the fields, the _meitheal _remained an important source of community resilience, especially for those facing hardship or misfortune. _Meitheal _participants might rally to help a widow or a farmer too sick to keep up with his chores. A _meitheal _might be needed to save crops from impending weather, to rebuild a house after a fire or to shore up a barn roof on the brink of collapse.

In The Stars of Ballymenone, folklorist Henry Glassie illustrates the _meitheal _spirit through the reflection of an old timer who says, “Here there is little excitement and no wealth, but here there are no final anxieties … We live in trust and charity and confidence. When troubles come, the neighbors will help.”

In 2020, with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, “meitheal” became a national watchword in Ireland, as urban and rural communities across the island banded together and tens of thousands volunteered to provide physical and social support to their most vulnerable neighbors. Reflecting on the power of Ireland’s _meitheal _spirit in times of crisis, Health Service Executive Director-General Paul Reid told the Irish Examiner, “It certainly has been demonstrated to me … the one thing that distinguishes us from other European countries is the power of our communities when we mobilise.”

Contributor: Erin Brown

| Source type | Full citation | Link (DOI or URL) |

|---|---|---|

|

Arensberg, Conrad M., & Solan T. Kimball. “The Relations of Kindred.” In Family and Community in Ireland, 59-75. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940. |

- | |

|

Glassie, Henry, The Stars of Balleymenone. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006. |

- | |

| Website |

Ryan, Ray. “The Spirit of Meitheal Has Been Revived by the Covid-19 Crisis.” Irish Examiner, March 30, 2020. https://www.irishexaminer.com/farming/arid-30990949.html. |

https://www.irishexaminer.com/farming/arid-30990949.html |

| Book |

O’Dowd, Anne, Meitheal: A Study of Co-operative Labour in Rural Ireland. Dublin: Folklore Council of Ireland, 1981. |

- |

| Book |

Sharkey, Olive. “Ch. 9: The Harvest.” In Old Days, Old Ways, 118-32. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1987. |

- |