Sontoku and the Hotoku Movement

| Giver: | Individual |

|---|---|

| Receiver: | - |

| Gift: | Voice/Advocacy |

| Approach: | Philanthropy |

| Issues: | 12. Responsible Consumption and Production, 2. Zero Hunger, 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth |

| Included in: | a Philosophy of Giving |

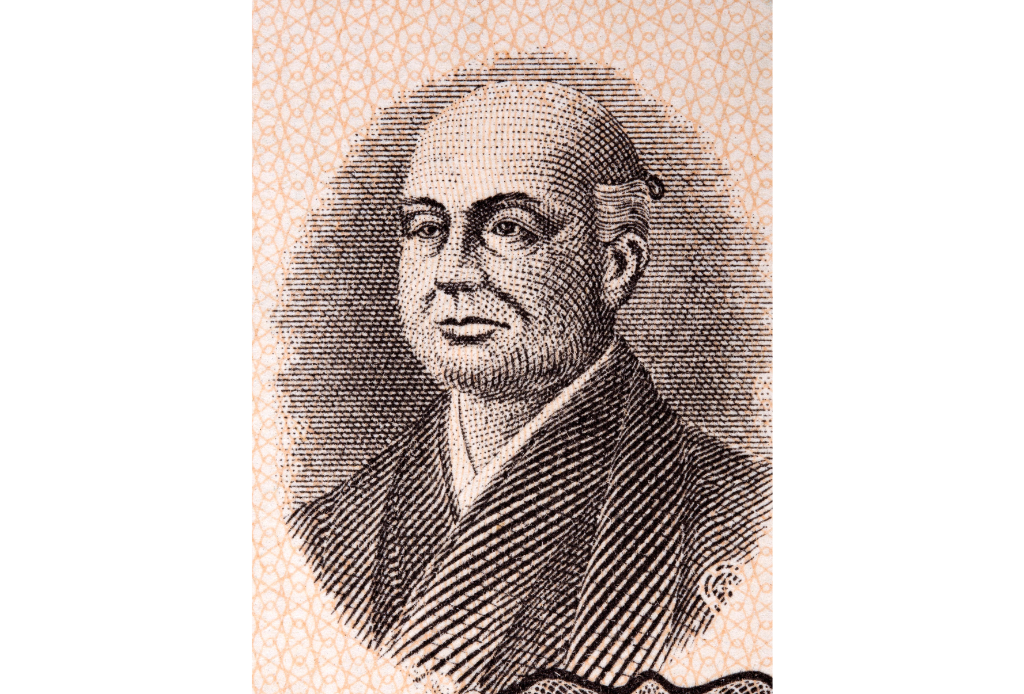

Ninomiya Sontoku (1787-1856) was a Japanese agronomist, economic philosopher and social reformer. Known as the “Peasant Sage of Japan,” Ninomiya based his economic system on the concept of Hotoku, a Japanese term meaning “repay the indebtedness.” A mix of Shinto, Buddhist and Confucian ethics, Ninomiya’s Hotoku Shiho (Hotoku philosophy) seeks to instill a sense of gratitude in its followers – toward their parents, their ancestors, their leaders, the gods and the natural world. Practitioners of Hotoku adhere to four guiding principles: kinrō (diligence), shisei (honesty), bundo (budgeting within one’s means) and suijō (altruism, or “giving back”). Rooted in concepts of reciprocity and mutual aid, Ninomiya’s ideas spurred a revolutionary land reform movement that raised hundreds of agricultural communities out of poverty, while eventually forming the basis of modern capitalism in Japan.

Taught Farmers the Power of Cooperation

Ninomiya was born into a peasant family in Kayama, Sagami Province. In 1791 a flood destroyed his father’s farm, plunging the family into poverty. Orphaned at the age of 16, Ninomiya went to live on his uncle’s farm, working the fields by day while educating himself at night. When his uncle refused to support his studies, Ninomiya cultivated oilseed rape on an unused plot of land in order to pay for the lamp oil he needed to continue.

When Ninomiya was 20 he returned to his native village. For the next four years he worked as a field hand, using his earnings to reacquire the land his family had lost. His success attracted the attention of Hattori Jūrobei, a local samurai, who hired Ninomiya to tutor his sons. During his tenure with Hattori, Ninomiya devised an idea for a financial cooperative, or gojōkō, through which he and the household servants could pool their resources. Hattori and his samurai peers soon established their own gojōkō based on Ninomiya’s model, creating what became the world’s first credit union.

In 1821 Hattori’s daimyō (feudal lord) hired Ninomiya to oversee the economic recuperation of the Sakuramachi district (modern day Tochigi Prefecture). Although the daimyo offered him a substantial grant, Ninomiya refused the money, believing the effort would only perpetuate the indadequate methods and work habits that had led to poor agricultural yields. Instead, he implemented a low-interest credit system, with the aim of instilling a sense of personal accountability in the peasants. At the same time, Ninomiya implemented a form of consensus-building, known as imokoji, in order to promote a spirit of cooperation among the farmers.

Laid Foundation of Modern Japanese Agriculture

Ninomiya’s radical approach revitalized the region, with potential rice output nearly doubling between 1823 and 1831. It also inspired similar programs in other rural villages throughout Japan. By the time of Ninomiya’s death in 1856, an estimated 600 villages had rejuvenated their agricultural output using his system. His Hotoku Shiho would also inspire a number of leading industrialists, including Shibusawa Eiichi (1840-1931), widely regarded as “the father of Japanese capitalism.”

In modern Japan, Ninomiya remains a symbol of the power of education to empower all individuals, regardless of origin or class. A statue of him as a young boy, reading a book while toting firewood on his back, still stands in front of elementary schools throughout the country. More significantly, Ninomiya’s philosophy of collaboration and reciprocity – of “giving back” to the world – remains a source of guidance and inspiration for social and environmental activists in the 21st century.

Contributor: Stephen Meyer

| Source type | Full citation | Link (DOI or URL) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication |

Garon, Sheldon. “Rethinking Modernization and Modernity in Japanese History: A Focus on State-Society Relations.” The Journal of Asian Studies 53, no. 2 (May 1994): 346-66. https://doi.org/10.2307/2059838. |

https://doi.org/10.2307/2059838 |

| Website |

Hattori, Yukiko. “Kanagawa: Ninomiya, an Icon of Learning and Ethics.” The Japan News, July 13, 2021. https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/features/japan-focus/20210713-46371/. |

https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/features/japan-focus/20210713-46371/ |

| Publication |

Maus, Tanya. “Rising Up and Saving the World: Ishii Jūji and the Ethics of Social Relief during the Mid-Meiji Period (1880-1887).” Japan Review, no. 25 (2013): 67-87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41959186. |

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41959186 |

| Book |

Takemura, Eiji. The Perception of Work in Tokugawa Japan: A Study of Ishida Baigan and Ninomiya Sontoku. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997. ISBN: 9780761808862. |

9780761808862 |

| Publication |

Yamauchi, Tomosaburo. “The Agricultural Ethics of Ninomiya Sontoku.” Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies 12, no. 2 (December 2015): 235-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.6163/tjeas.2015.12(2)235. |

http://dx.doi.org/10.6163/tjeas.2015.12(2)235 |